- Danny Cheng, better known as Scud, has been making films for 16 years and has decided to stop after his 10th – Naked Nations: Hong Kong Tribe

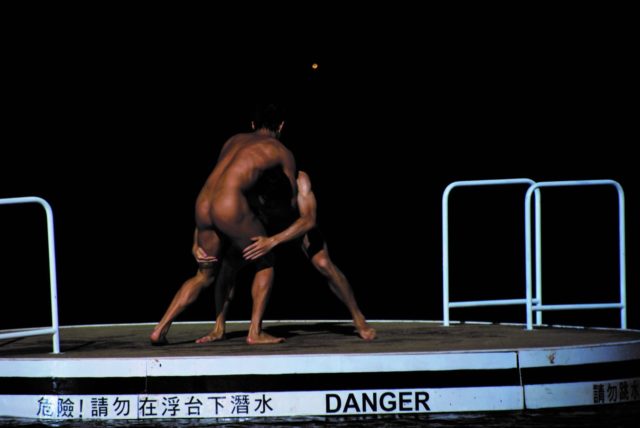

- Scud is known for sexually explicit films depicting drug use, death and depression, and is a pioneer of Asian queer cinema

Renowned queer filmmaker Danny Cheng Wan-cheung may be leaving Hong Kong and even stepping back from making films, but he is not too sad about it.

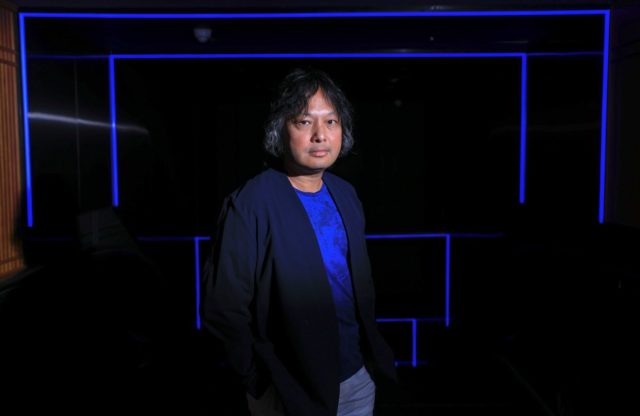

Resting on an armchair in the music lounge of Eaton HK in Jordan, Cheng, who goes by his artist name Scud, is still energetic, even after hours of media interviews. He is promoting the mini retrospective of his films by the Hong Kong Lesbian & Gay Film Festival (HKLGFF), of which he is this year’s “Director in Focus”.

Dressed in a blue blazer and white canvas shoes, he jokes about his growing belly and how much he has aged since he started making movies 16 years ago.

Cheng’s greying hair peeks out from underneath a bed of permed and dyed black curls, as part of his character’s look in his upcoming film Naked Nations: Hong Kong Tribe, which will also be his final feature.

With his jolly laughter and quirky sense of humour, it might be jarring for the uninitiated to learn that Cheng’s films predominantly deal with topics of death, drugs and depression. The director also does not at all shy away from full-frontal nudity, graphic imagery and same-sex eroticism.

With his debut City Without Baseball (2008), based on Hong Kong’s only amateur baseball team, and hits such as Amphetamine (2010) and Thirty Years of Adonis (2018), Cheng is regarded as one of the pioneers of queer Asian cinema. His films garnered a strong fan base in Taiwan, and he was the first Q-Hugo Award recipient in the 49th Chicago International Film Festival.

As tribute to his contributions, the HKLGFF has lined up a Scud retrospective, premiering his two new films Bodyshop (2022) and Apostles (2022), and also screening Permanent Residence (2009) and Amphetamine. The director is set to be in attendance for all his screenings.

Variety broke the news in May that Cheng would be retiring after releasing two new films and completing his 10th picture. Cheng also announced in August that he will be leaving Hong Kong.

“It is true,” he says with a chuckle when we sit down for this interview. “However, I would like to clarify that I am retiring from filmmaking, but I am not retiring.”

Despite outcry from his dedicated audiences, filmmaking is a chapter of his life that eventually has to come to a close.

“I’m so ashamed but anyone can figure it out: I’m financially exhausted by my 16 years of filmmaking,” says Cheng, who always writes, directs and produces his own projects.

“But to me that was what I wanted to do – almost, what I had to do. If I was not making films, I might have died long ago.” He takes a pause. “Film saved my life. That was 16 years ago. I was a very depressed person.”

Of course, financial concerns were not the only reason. Cheng made films because he had stories to tell, not because he wanted to make money, he emphasises. But now, he feels that he is almost done pursuing what he has set out to do, especially with the exhaustingly cathartic completion of his ninth film, Apostles.

“Death has long been the main topic of my films, and I’ve poured all my thoughts and visions into Apostles. After this, I feel that there are no more films that I have to make in my life,” he says.

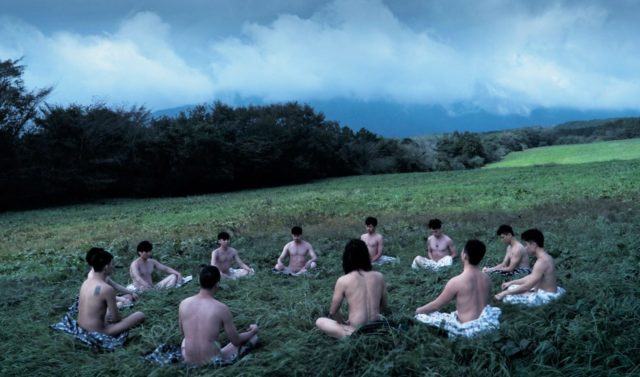

A deep-dive into the meaning of life and death, Apostles is visually striking, with plenty of biblical and ancient Greek imagery. In the film, a scholar, who claims to be Plato’s apostle, invites 12 young men into his secluded manor to explore the theme of death through extreme practices.

“I would say for Apostles, only I have the ability, or the vision, to make a film like this nowadays. It is the most symbolic of my style,” says Cheng.

Bodyshop, another film made during the same year, explores the notion of the afterlife, intertwining a real paranormal experience by actor Adonis He Fei with the story of the ghost of a young soldier.

Cheng migrated to Hong Kong from Guangzhou when he was 13 years old, and has lived in the city more or less ever since. After 22 years working in the IT industry, and a four-year stint in Australia, he moved back to Hong Kong in 2005 to make his first movie.

But audiences hoping to watch a “conventional” Hong Kong production might end up surprised, or disappointed, says Cheng. “It gets tricky when I’m introduced as a Hong Kong filmmaker. I’m a Hongkonger all right, but I don’t consider myself a maker of Hong Kong films. I think that is very different.”

Looking back, Cheng feels that he has left an impact on Asian cinema by pushing boundaries on what can be shown on the silver screen.

30 Years of Adonis was widely screened in Thai cinemas, while Bodyshop and Apostles recently passed the Hong Kong censors on their first attempt. However, Cheng remains pessimistic about a wider release for his films in Hong Kong.

“If it hasn’t happened in so many years, I don’t think it will happen. However I am grateful that Hong Kong audiences can see them on the big screen, although it is in a film festival. I look forward to their reactions. To me, that was something I was doubting one or two years ago,” he says.

So where to next for the filmmaker? He has no final destination in mind, but he will first fly to Taiwan to attend premieres for his two new films, before heading to Japan for a break, then spending a few months in Thailand for the post-production of Naked Nations.

Cheng does not shy away from the reason he is leaving Hong Kong. Contrary to popular belief, the main force driving him away is pandemic policies instead of the crackdown on freedom of expression.

Cheng sees being in IT and making movies as two chapters in his life, and he is already looking forward to the third. “My destiny will tell me what’s next for me,” he says. “I still hope to accomplish one more thing before my body gets too tired, but I don’t know what that is yet.”

Cheng has bought a one-way ticket out of Hong Kong, but first he will finish his 10th and final film, Naked Nations: Hong Kong Tribe. Perhaps his most experimental yet, it will be shot entirely on an iPhone 13 with a full Hong Kong cast, and no screenplay.

The film will be about the past three years in Hong Kong. But don’t expect to see it within the next five years, says Cheng with a cheeky smile, as he will be taking his time with the post-production.

“Naked Nations will be about uncertainty. I want to demonstrate how uncertain we are collectively in this place,” he explains. “But I expect the film to be hopeful too. We need to be hopeful in dire situations. The worse the times we are experiencing, the more hopeful we have to be.”

The Hong Kong Lesbian & Gay Film Festival runs through October 1.